Robin Williams reacts to how Popeye was received.

To Clear A Few Things Up

A few myths need to be dispelled about the 1980 Robin Williams film, Popeye.

- It was NOT a boxoffice failure. It was made for 20 million and grossed well over 60 million. While deemed a “disappointment” by Paramount Pictures, it hardly failed.

2. It is NOT Robin Williams’s worst film. I will argue it is his best, hands down.

Like Williams and its director, the film paid a price for breaking away from formula. Popeye is fucking art, so there, I said it.

Popeye fought Cynema and lost the first few battles, but I think it won the war. It was Robin Williams’s first film, and almost his last. It’s been called a mess, incomprehensible, a misfire, a disaster and a bomb. Bear with me as I show how this unique film stands up against Cynema. I’ll also lay out how this film reflects the present attitudes between industry and audience. Years after I declared Popeye as Williams’s best film, Vanity Fair published a piece that supported my claim: https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2014/08/robin-williams-popeye

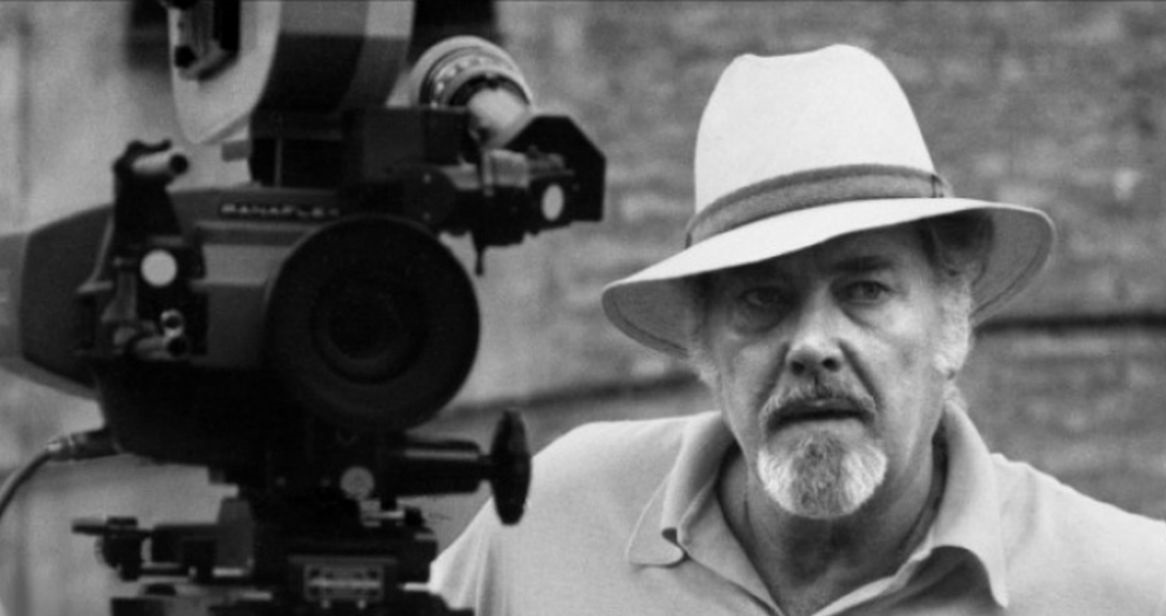

Director Robert Altman

From the start of Robert Altman’s directing career in TV, he was known for putting the independent in independent filmmaking. His stars either loved or despised him. Robin Williams almost quit Popeye several times because of conflicts with Altman. Altman embraced a naturalistic style to film and the acting method– not all that different from Williams’s chaos theory style of comedy.

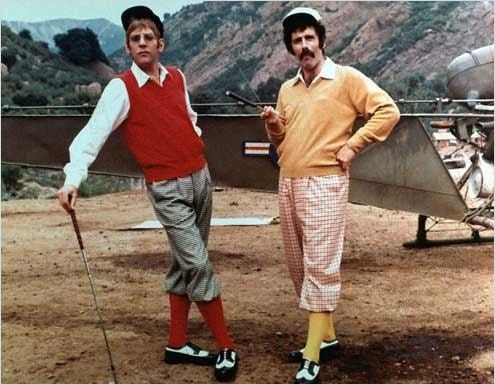

Donald Sutherland (L) Elliot Gould (R) onset of Altman’s hit, MASH

Director Auteur

The director often clashed with producers, studios and actors. He faced mutiny on perhaps his best known and commercially successful film, MASH. Elliot Gould and Donald Sutherland lobbied to have him fired. They opposed his freestyle approach to acting, allowing the actor to take responsibility for the development of their character. Altman had a number of “patron saints” who wanted to see him deliver another commercial success and be accepted by mainstream Hollywood.

Fellow director, Robert Dornhelm once said the following of in describing Altman’s reaction to distributor interference in the editing process of his film Short Cuts:

“Bob just thought the Antichrist was trying to destroy his art. They were well-meaning people who wanted him to get what he deserved, which was a big commercial hit. But when it came down to the art or the money, he was with the art.”

We had a director who stood for the artistic process with a thinly veiled contempt for the industry that he fed and fed him. It appears that Altman cared little for financial success and wanted art to trump commercial appeal. He was a anomaly in Hollywood. His characters were imperfect, their dialogue overlapped in dizzying rapid fire volleys. Altman’s directorial style let a film unfold as it may, not according to the structure of a three act formula and a script hitting all of the proper beats. Robert favored character motivation and intricate relationships over detailed plots.

This is why Popeye succeeds.

Robin Williams

Williams was burning through stand up midways for some time before he was unleashed as a guest star on the hit 70s sitcom, Happy Days. Mork from Ork was a fast talking, space alien who appeared in the latter years of Happy Days, after it had famously and literally “jumped the shark.” He eclipsed his famous co stars and stole the show. It wasn’t long before a spin off was commissioned with Mork and Mindy added to the ABC lineup.

Williams was a dispensary of catch phrases. Overnight, American teens aped his shtick. Fellow stand up comedians patterned his shotgun style. I remember Williams on The Tonight Show with host Johnny Carson desperately trying to keep up with him. It was a telling moment between the old comic guard and this new, wild upstart. Carson was out of his depth.

I remembered thinking, “Johnny just shut up and let this guy go.” Not only couldn’t Carson keep up, he was exposed as a scripted comic trying too hard to earn a seat at the cool kid lunch table.

Williams reducing Carson to insignificance in less than five minutes on the Tonight Show.

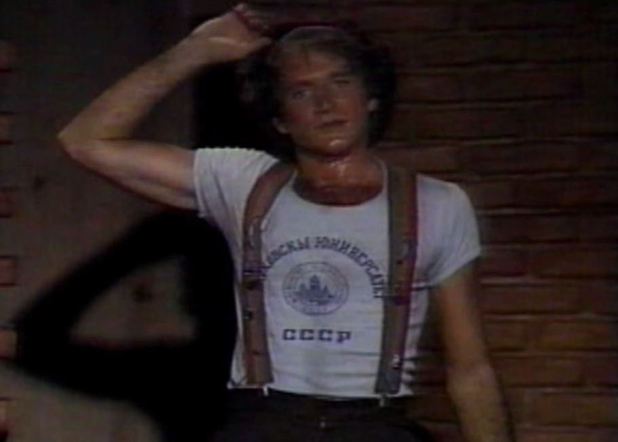

The rainbow suspenders, sweat and pure adrenaline that defined Williams in stand up comedy.

Hollywood never knew what to do with Williams. Mork and Mindy was a paycheck–a mediocre sitcom that existed only to showcase Williams.

Mediocrity vs. Risk

The sitcom was a safe delivery system for American viewers who could experience Williams comfortably and avoid his wild, drug-fueled stand up routines that made must see cable TV. Williams was X-rated for anyone over 15.

Films like RV, The Survivors, Flubber, Old Dogs, Hook and even Mrs. Doubtfire, were bland, safe, commercial pieces and consequently, the kind that Williams railed against. While Patch Adams meant well, it’s a saccharine excuse to showcase Williams with a heart of gold. Dead Poets Society had a “walk to a different tune” message, but again made Williams safe. However, when NBC’s Michael Scott from The Office believes this film is the height of inspiration, you see what I mean.

These films were pay checks and what the actor is most known for. It was no secret he was saddened at the prospect of a Mrs. Doubtfire sequel before his death, having no respect for the material that gave him one of his biggest hits.

In many ways he was Altman’s artistic doppelgänger. Both needed commercial success, yet resented it. Both wanted the ability to explore the artistry of film and push the medium in their own ways. They found themselves pushing back against the industry and audience expectation. Williams achieved awards and nominations for Awakenings, The Fisher King and Good Morning Vitenam, Good Will Hunting, but he always seemed to be searching for “something else.” Films like Baron Munchausen or uncredited, inspired cameos in Shakes the Clown seemed like void-filling. He explored serious takes in Moscow on the Hudson, One Hour Photo and Insomnia, but again, Hollywood had no idea how to package Williams.

When it came time to make his first film and breaking the confines of a dull sitcom, Williams chose Popeye.

“Don’t you know Popeye wasn’t good for anybody?!” — Williams in a stand up routine bashing his film.

Dustin Hoffman was vetted for the role of the King Features comic sailor from Thimble Theater and eventually passed. Williams came to the attention of producer of Evans after Mork and Mindy shot to the top of the TV heap. Altman was signed and Williams’s scattered energy seemed a prefect fit for Altman’s loose hand in allowing his actors build their characters. Altman went to work immediately against the studio system. What would or should Popeye be? A musical was a daring move, but emboldened by the success of Annie, Paramount and Disney rolled the dice.

Here is where Popeye emerges as a true piece of art, and despite its poor critical and popular reception, round house punched Cynema in the face.

Altman assembled his “team of rivals”, a patchwork of artists not known for mainstream success. Altman was about WORLD BUILDING, and his movie would not be shot on some studio sound stage. Spielberg found success with insisting Jaws be shot on the open Atlantic, far from the pools, tanks and executives of Universal Studios. Altman was about to take this a step further.

Fringe cartoonist, playwright and screenwriter , Jules Feiffer was selected to write the script. Mainstream success hit Feiffer when his unproduced play, Carnal Knowledge was adapted to screen with Mike Nichols directing. This led to the job of Popeye‘s screenwriter.

The Disney Anti-Disney Film

Popeye’s script is not so much a three act screenplay than it is a character study. It seems almost EVERYONE has something to say and contributes to this baroque world. The film opens with an odd assortment of townsfolk breaking into a dour anthem (the soundtrack and songs to be discussed). The characters seep from the woodwork, between the buildings and into view. The first five minutes show that Popeye was not going to be the Disney type family musical.

Mary Poppins it ain’t.

The opening is not some show-stopping tune. Instead Altman BRINGS US into this world and we have no idea where this is or even a time frame. Is it World War II? Is it the 1930s? Is it modern day and a town that time forgot? We have no idea and that’s just what Altman wants. That isn’t important… settling into this world is.

Watch the opening and see the film release its characters. They filter in, dotting the streets and layering into the set. We are seeing something special, and I knew this while watching it in the theater back in 1981. Many of the “extras” were not professional actors, but rather circus and vaudeville performers. Watch the performer chasing his hat in the old slapstick routine, the mayor and his wife all regal and strutting pompously while Altman staple, Paul Dooley plays Wimpy in hamburger bliss.

This is movie magic.

The set of Sweethaven, built from the ground up for the film.

The town of Sweethaven today…now renamed “Popeye Village” and a famous tourist attraction.

World Building

Altman ordered the construction of an entire town for this film. Under the art design of Wolf Kroeger, the town of Sweethaven was a collection of odd angles, sagging rooftops and drab buildings clinging to the Maltese cliffside. This was not a set…it was a living, breathing town and it is still used today as a popular tourist attraction called Popeye Village.

Sweethaven was assembled with imported lumber–each building handcrafted for its own unique look. The white cliffs were Altman’s canvass and he took care to populate these buildings with people who fit their unique character. This is true love and passion for filmmaking. Today we can imagine how this would go. Most of the town would be a CGI rendering, and existing structures on a lot. However, this film would not be made today. No studio would take such a creative risk and many look with scorn on Paramount’s folly over thirty years ago.

The clip above shows how Altman paints his canvass. The song “Everything Is Food” is not meant to be a polished, slick tune. It’s the breath of a town that has so little to look forward to, that food is one of the few, basic enjoyments they all share as a community. Altman allows this to unfold slowly, fitting each scene with a unique character while Captain Bluto, Popeye’s nemesis, observes with a gluttonous eye from above. Slapstick, physical hijinks all happen in a quiet mania orbiting around William’s Popeye as he tries to find a quiet place to enjoy a hamburger. Not a word is spoken by Williams, but his face and body language speak volumes.

EC Segar’s Popeye was a world renowned figure. His crusty image, swollen forearms and Spinach addiction made it almost impossible for a real-life translation. It would never measure up.

Williams did it.

He inhabits Popeye. We feel for him. He’s surrounded by a confederacy of dunces, looking for his father and respectful of the people around him. He possesses a quiet dignity and humility. Popeye’s a simple man and the cafe scene shows us exactly who he is, and how Williams had a role that utilized every aspect of his talents.

I was in eighth grade when I saw this film. It was customary to see a big film with a group of friends. I was the only one out of six kids who liked it. I listened to people grumbling as the full house emptied . When I declared my enjoyment of the movie, I might as well had been beaten down. Yet, for all the complaints, the audience seemed quite entertained while the movies was playing.

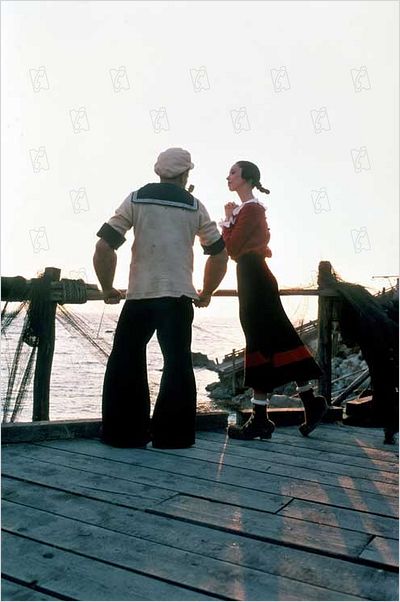

A moment that stood out was Shelly Duvall’s entrance as Olive Oyl. When those big boots clomped all horse-like down the steps and the camera raised up to reveal the actress–there was a collective gasp from the sold out house. Then silence as they realized they were looking at Olive Oyl. Not an actress. By God, this woman WAS Popeye’s beanpole girlfriend.

I never heard such exasperation from an audience again until 1986 when James Cameron revealed the majesty of the Queen Alien in Aliens and then over 20 years later when the T-Rex busted out of its jail in the original Jurassic Park. Duvall was a living special effect and that gasp said only one thing: “How the hell did they do that?”

When you ask most who saw the film back in the day, the number one gripe is something like “It wasn’t what I expected.” So what does that mean? This was a time before comic books hijacked cinema. Were they expecting a more consumer film? Popeye didn’t beat up enough people? It was boring? The detractors were right about one thing: it was NOT what anyone expected. I’m sure Paramount and Disney were popping antacids after an executive screening. The biggest film of the Christmas season was a fat turkey and they had to think fast to ensure they broke even.

Layered Characters and Art

Altman allows the relationship between Olive and Popeye to truly take shape. The dinner table scene where Popeye is subjected to a dialogue smorgasbord is classic Altman. Characters talk over one another. Geezil professes his hatred for Wimpy, Wimpy dispenses marriage advice to Olive, Olive bitches over glasses, knives and people picking on her fiancee, Bluto. Nana Oyl flits in and out with daffy surprise while her husband Cole demands apologies and gives his son Castor a few ‘atta boys for putting his sister in her place. There are at least four different conversations going full force, and in the middle of it all Popeye never gets a bite to eat. Williams hardly utters a word, his face and body doing all of the heavy lifting, and the final result is just beautiful.

Williams was at his height in this film, and he didn’t know it.

We often hear great dialogue (if you’re listening for it) off screen or just under breath. When the short, rotund mayor walks Mutt and Jeff style with his towering wife to Olive’s very prestigious engagement party, he timidly reminds her, “remember my dear, tonight it’s my turn to be tall.” Another off-screen exchange between some unseen couple as the town settles in for the night. “Don’t forget to put the cat out, dear,” a nasal wife nags her husband. “We don’t have a cat!” he snipes back.

Williams and his ability to ad lib was harnessed properly. Popeye was known for his under the breath mutterings. When Olive jumps into his arms frightened, we hear him mutter, “shouldn’t we have dinner first?” He later reads a note pinned to the abandoned “infink” Sweetpea. The baby blabbered something that sounded like “baby” while Williams read the note. He fires right back, “You’re a baby, it says so right here.”

When Nana Oyl exclaims absent-minded over something, Williams looks at the mailbox which has “Oyl” printed on it. “Oyl,” he grumbles. “That explains it. She’s down a quart.”

The moments go on throughout the entire film. You have to work for these nuggets of genius. You must listen. And the only way to do this, is to surrender yourself to the film. Let it in. Experience it.

Duvall was robbed of an Oscar for her channeling of Olive. The song “He Needs Me” is often cited as “terrible.” Yet, Olive was once described in the comics as “The Terror of the High C’s.” Olive can’t sing, and Altman preserved this. He could have easily dubbed the song portion to a proper singer. Instead Duvall is allowed to sing her love for Popeye as neighbors close their windows and she dances like a goony stork. This is love for a character, a director staying true to his screenwriter and allowing full trust to his actress. The only way to appreciate it is to experience it.

This brings me to the soundtrack.

Harry Nilsson, scoring major street credit for “Everybody’s Talkin’ At Me” from the Oscar winning Midnight Cowboy was brought in to write the songs. Like Williams and Altman, Nilsson was known for alcohol and drug abuse. He clashed with Altman and left the picture early, leaving Van Dyke Parks to finish out the job. The film’s soundtrack was critically savaged. Yet, the clumsiness of the songs gives the film its soul. This was so anti-Disney. This was not Annie. Audiences didn’t get it. They wanted polished. They wanted Big Mac show stopping tunes. What they got was awkward, bumbling and sweet.

That big, black, flat disc is a record, folks…and the soundtrack to the movie, Popeye.

Nilsson’s “I Yam What I Yam” is Popeye’s declaration of self. It’s this song that pulls all of the strings together. The world that Altman built gets turned inside out, and yet, we hardly notice. When we meet the good women of Sweethaven in the opening of the film, they are socialites. The leader is the mayor’s wife. By the time we get to “I Yam What I Yam” we find they are turning tricks in a casino that doubles as the town brothel. Altman doesn’t make a big deal out of this. He doesn’t beat it over the our heads. Instead, he lets it up to us to discover it and…HE NEVER EXPLAINS IT.

The Altman Style

Altman allows us to identify with Popeye who refuses to cave to the temptation of exploiting Sweetpea’s psychic powers. “Wrong is wrong, even if it helps ya!” he barks at Olive who should know better. He’s propositioned by the Sweethaven wives, now whores, who earlier turned their backs and shunned him at Olive’s engagement party.

The scene is clear: Popeye has a strong moral center. That’s it. Again, the world around him is the issue. We always know where we stand with him, and that folks, is the magic of Robin Williams and Robert Altman.

Altman delivered a film that ran just under two hours. It is not a film that is all over the place. Follow Popeye and you never get lost. It’s Popeye’s journey, but unfortunately, audiences needed their hands held. Today’s audiences now need to spoon fed like baby Sweetpea and no longer wish to discover or ask questions. They want it all delivered and tied up.

Popeye didn’t work because audiences didn’t understand that it wasn’t about watching a film, it was about walking through one and exploring it. Altman invited audiences to Sweethaven. While the title of the film is Popeye it’s really about everyone in Sweethaven, because each and every one of them has a story. The actors Altman assembled inhabited their roles.

There isn’t a single bad performance in this film.

Popeye is a handcrafted film. It was built, constructed and then allowed to be inhabited by beings with souls. It creaks and it rocks and sometimes it even stumbles. It’s exactly what Altman wanted. I’ve heard there is at least another hour of footage missing from the film. No doubt Altman was forced to bring the film in under two hours. Likely he fought having his film cut. It would be wonderful to find this footage and see a restored print of this film.

So what was the final result? The film was released Christmas, 1980. It did reasonably well, but was deemed and perceived a critical and financial disappointment. It didn’t inspire action figures, calendars, or lines at conventions. It wasn’t launched at Comic-Con. There were no plans for sequels and to this day, no plans for a remake, reboot or bullshit “re-imagining.”

No, Popeye, like the titular sailor, is a loner. Williams went on to trash the film in interviews and stand up routines. It was clear he wasn’t proud of soulless packaged claptrap like RV, Toys, Hook, Jumanji, Mrs. Doubtfire or even his turns in the Night at the Museum films. They were paychecks, and they were some of his most successful films.

His second film took a darker comedic tone in the successful The World According to Garp. He bounced around to other films that he had thrown at him before Popeye and passed.

While Williams complained, his film career is regarded as successful. He returned with great acclaim to stand up at The Met and on Broadway. Popeye didn’t damage him. Williams died in 2014.

That wasn’t the case for Robert Altman. The film took one hell of a critical drubbing. For many in the industry, it was the last straw. If he was going to fight the system, then the system would turn its back. Popeye was to enhance his commercial appeal. Its failure was seen as auteur self-sabotage. He tried several other pictures, all disappointments, before finding some success with cable TV and the series Tanner ’88. Basically, Altman was exiled from Hollywood and he would be gone from the majors for a decade.

He returned with 1992’s hit Hollywood satire, The Player, which gave a huge middle finger to the filmmaking process and big studios destroying the artistic process. He garnered a Best Director nomination and continued to work until his death in 2006.

Both men leave us with a film that is a perfect storm of will, vision, creativity, and insanity. It is deliberately imperfect. It welcomed an audience with open minds and hearts and asked them to enjoy something for the sake of enjoyment.

If that isn’t Anti-Cynema, then I don’t know what is.

Listen to my Cynema podcast found on iTunes, YouTube, Stitcher, Spotify and iHeart Radio.